What is carbonic maceration?

What is carbonic maceration? Article written by Christina Pickard for Wine Enthusiast

Few terms in the wine world will get you labeled a geek more swiftly than “carbonic maceration.” Just the sound of it conjures images of mad scientists and sci-fi superheroes.

Despite its high-tech name, carbonic maceration, or simply “carbonic” (carbo if you’re French, or cab mac if you’re Australian), is an important winemaking technique. It’s worth learning about, not just because it’ll make you sound like a smarty pants, but because the method is more widespread than ever thanks a growing trend toward lighter, fresher reds.

Carbonic maceration can completely change a wine’s style and flavor profile. If you’ve ever tried a red wine that bounced brightly out of the glass with an ultra-fruity bubble-gum aroma or crunched lightly with cinnamon, vanilla and earthy, stemmy flavors, it’s likely you’ve encountered carbonic maceration.

Carbonic maceration is a winemaking technique that’s applied primarily to light- to medium-bodied red wines to make them fruitier and to soften their tannins.

Most wine transforms from grape juice into alcohol via a yeast fermentation. Bunches of grapes are picked, destemmed and crushed. The yeast, whether naturally present on the grape skins or added by winemakers, “eat” the natural sugars in the grape juice and converts them into alcohol.

In carbonic maceration, however, the initial fermentation is not caused by yeast, but instead occurs intracellularly, or from the inside out. This method involves filling a sealed vessel with carbon dioxide and then adding whole, intact bunches of grapes.

Grape that has experienced carbonic maceration (left) showcasing darker flesh than normal grape (right) / Photo by Andrew Thomas Lee, courtesy Martha Stoumen

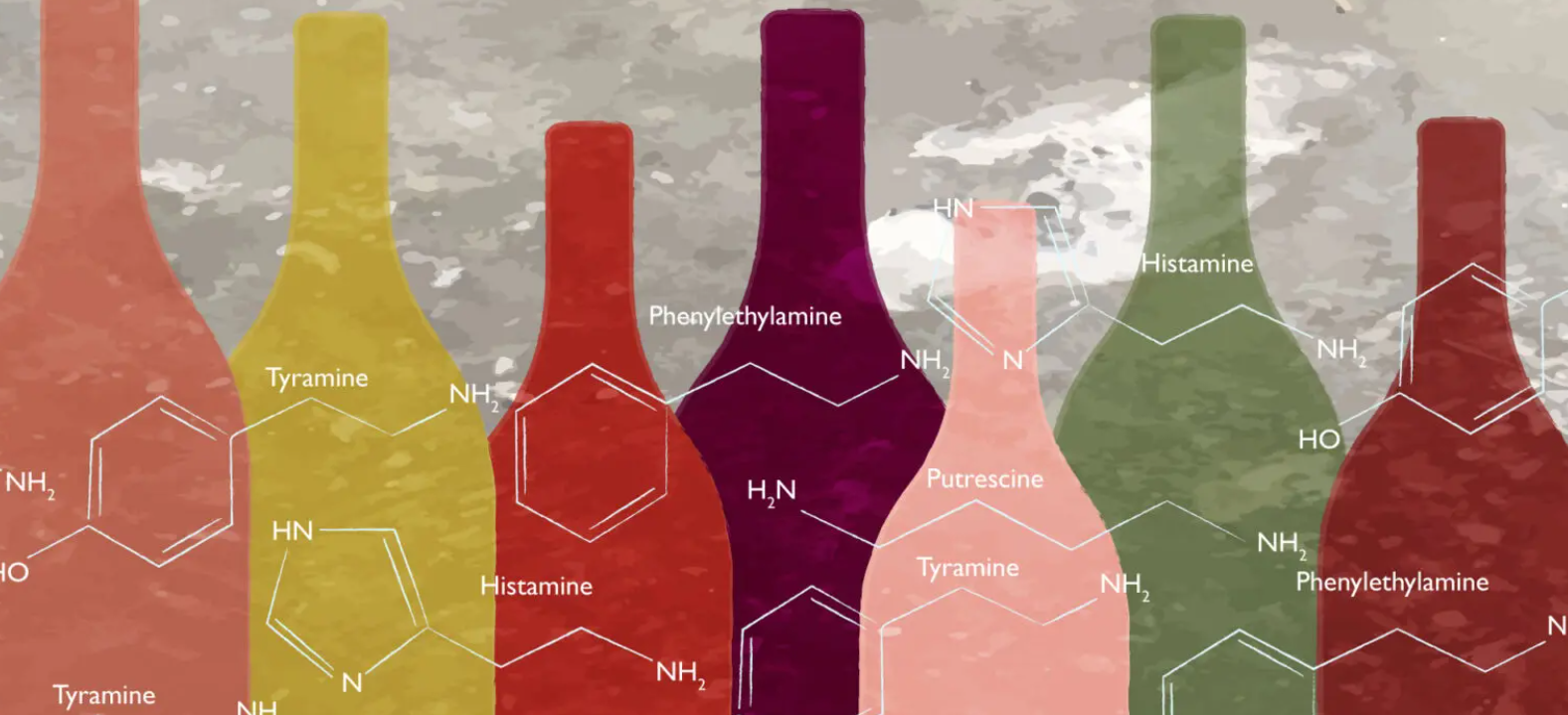

In this oxygen-free environment, the berries begin to ferment from the inside. They use the available CO2 to break down sugars and malic acid (one of the main acids in grapes) and produces alcohol along with a range of compounds that affect the wine’s final flavor.

At the same time, polyphenols, known to most as tannins and anthocyanins, make their way from the grapes’ skin to the pulp, which turn the white flesh to a pink color. Once the alcohol reaches 2%, the berries burst, releasing their juice naturally. A normal yeast fermentation will then finish the job.

Add all this together and the result is a wine that’s light in color with low levels of acidity and tannins, and highly fruity aromatics, intended generally to drink young.

Who's behind it?

Carbonic maceration, at least in partial form, occurs naturally in any vessel where oxygen is limited, carbon dioxide is rich, and a percentage of berries are intact. The science is as ancient as winemaking itself.

But modern, controlled maceration carbonique was invented in the Beaujolais region of France, just south of Burgundy, where the light- to medium-bodied Gamay grape rules. In the mid-to-late 20th century, Beaujolais’s reputation was elevated thanks to carbonic macerated wines, particularly Beaujolais Nouveau, an early-drinking wine released just weeks after fermentation is complete.

The man credited with the discovery of carbonic maceration is French scientist Michel Flanzy who used carbon dioxide as a grape preservation technique in 1934. It didn’t gain speed until the 1960s, however.

Around the same time, Jules Chauvet, a négociant and chemist from Beaujolais widely considered the godfather of natural wine, also made great strides with his studies in semi-carbonic maceration of Gamay grown on Beaujolais’s granite soils. The technique is used widely by natural winemakers today.

In 1986, Australian winemaker Stephen Hickinbotham patented a method that involved using a sealed plastic bag to contain the juice and dry ice to create carbon dioxide.

Thanks, Christina Pickard, for this interesting learning. Cheers to a new week and to more knowledge!