Why Does Some Wine Get Better with Age?

Why Does Some Wine Get Better with Age? Article by David W. Brown for Wine Enthusiast

Few wines are ageworthy. Most—even very good ones—are made to be uncorked within the first year after bottling. Their tasting characteristics reflect this. In the case of reds, tannins— the compounds astringent on the palate— are usually lower, and acidity as well, but red fruits are pronounced. Whites, meanwhile, might have high acidity and simple notes of citrus and green apple.

But what wines are made for the long haul? And how do you know?

The drivers sustaining these wines that can improve over a decade or more are acidity, alcohol, and for reds, tannin and for sweet wines, sugar. Every bottle of quality wine is a self-contained world where time moves slowly (larger formats, such as magnums, slow the process due to the ratio of air-to-wine in a given bottle). They should be cellared in darkness at temperatures between 50–59°F.

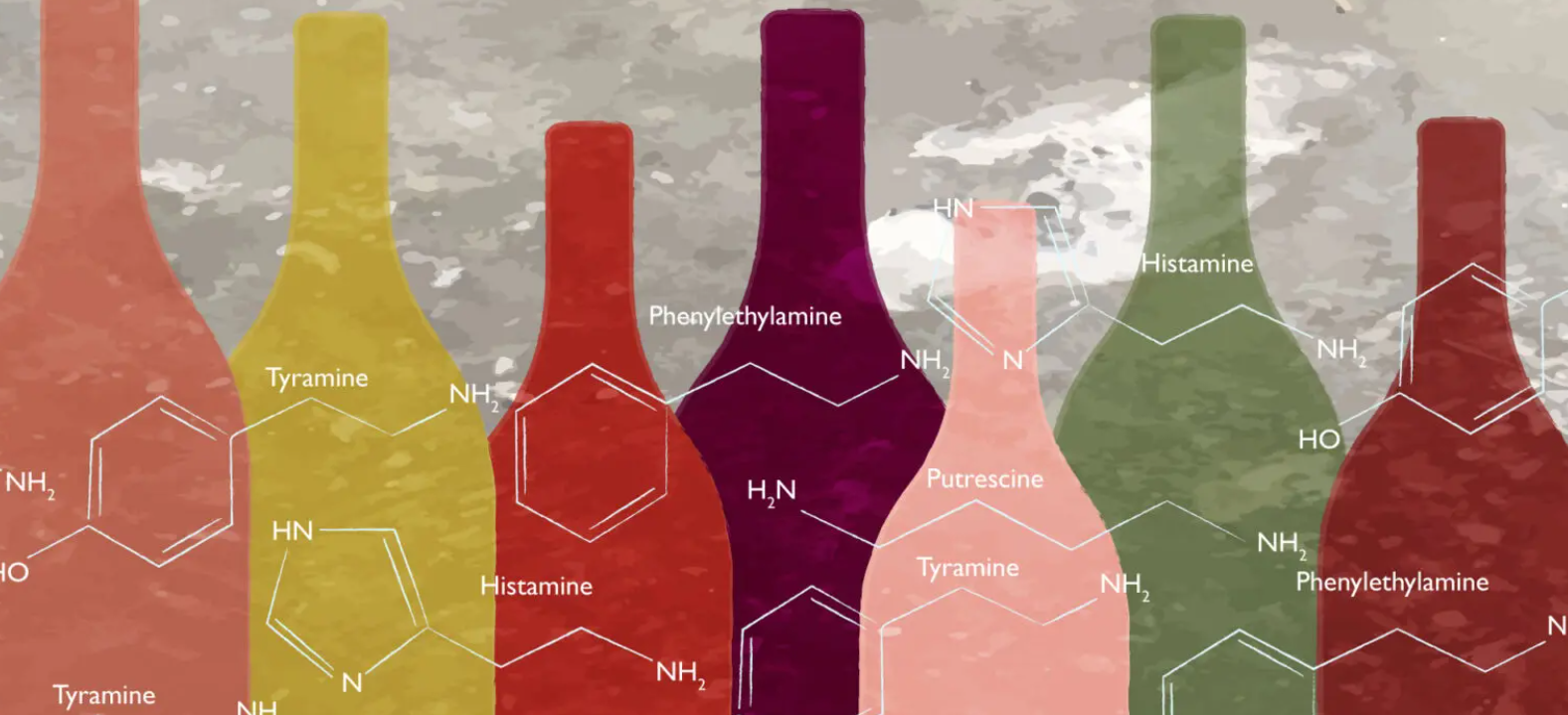

This allows the chemical reactions to proceed naturally. The interplay of those structural components, flavors and microbes will yield new aromas and tastes possible only with time—like tobacco, petrol and dried fruits may reveal themselves eventually. You don’t get those notes every day.

But you need not wait years to enjoy that expensive bottle. Many winemakers work to ensure a wine can be enjoyed now, or 30 years from now.

“If you get the structure right, the ageability will fall in line, and the approachability will fall in line,” Jeff Smith, the owner of Hourglass Wines, a cult Napa Valley winery, tells me. Certain winemaking techniques can bond abrasive tannins with color compounds, allowing uncorking in youth or longevity in the cellar. Hourglass uses precise manipulation of temperatures during fermentation in order to release color compounds—monomeric anthocyanins, specifically—that bond with tannins.

“If you understand organic chemistry and how to translate that into the actual winemaking discipline, you can have your cake and eat it, too.”

You can also age Champagnes—and not just vintage ones. “Even nonvintage champagnes can age beautifully,” says Émilien Boutillat, the chef-de-cave of Piper-Heidsieck, founded in 1785.

To prove it, we taste several nonvintage Champagnes in their Essentiel collection, as well as older Brut bottles, whose base wines go back decades. If you were to buy a bottle on store shelves today, you would be drinking a nonvintage wine, the foundation of which was grown and pressed in 2018. It possesses the signature characteristics of Piper-Heidsieck: a notable vibrancy and fresh fruits. When we dug further back, to a nonvintage bottle with a 2012 base, however, we found shyer fruit, but honeyed notes and more pronounced toast.

“It is still fresh,” he says, “but it is on the line in-between of a wine you enjoy for its youth, and maturity. It still has bite.”

Backward in time we go—trying wines with bases from 2010, 1995, 1985—and the notes change markedly: coffee beans, dry apricots, and lemon pie. Consistent throughout is a lovely line of acidity, vibrancy and freshness.

“It’s really a matter of taste,” Boutillat says. “Each one of us is different. It’s up to you to keep your wine as long as you’d like.”

Thank you, David, for this head up!