Sulfites, legs and other misinformation campaigns in wine

Article in Wine Enthusiast by Caroline Hatchett

As with diet advice and vaccine science, wine professionals aren’t immune to the human tendency to cling to misinformation. Myths abound. Bad information is passed from consumer to consumer, restaurant manager to fledgling wine pro, and marketing companies to the masses. They stick, because it’s often easier to remember bad information than investigate everything. It’s a situation complicated by the intimidating and esoteric nature of wine.

“We often assume sources are reliable,” says Northwestern University psychology professor David Rapp in a study of why people rely on inaccurate information. “It’s not that people are lazy, though that could certainly contribute to the problem. It’s the computational task of evaluating everything that is arduous and difficult, as we attempt to preserve resources for when we really need them.”

Wine myths are often born when everyday drinking experiences are hard, or require an expert level of knowledge to explain.

Wine legs, decanting and lunar cycles

“One claim I’m wary of is the idea that certain wines taste better on certain days based on the lunar calendar,” says Drew Brady, wine director of New York City’s Overthrow Hospitality. This refers to the belief among biodynamic practitioners that the lunar cycle and its elemental signs (earth, air, water and fire) influence how a wine tastes on corresponding days (deemed root, flower, leaf or fruit days).

“There is no shortage of passionate arguments on both sides, but I’m really hard-pressed to believe that a red wine tastes better on a ‘fruit day’ than it does on ‘root day,’ ” he says. “I’m all in on low-intervention winemaking and biodynamic farming, but once it’s in the bottle, I’m settled…unless I’m missing something.”

While at least one study has debunked the lunar cycle’s influence on taste, many Demeter-certified wineries won’t host tastings on certain days, and apps instruct users when to enjoy or avoid certain wines.

Most misconceptions in wine, though, are a lot less mystical and much easier to refute.

In the tasting room of Frichette Winery in Benton City, Washington, co-owner and co-winemaker Shae Frichette observes guests swirling glasses of Petite Verdot and Malbec, saying “Ooooh, look at the legs. This is a good wine.”

Legs, the rivulets that run down the sides of a glass, indicate a wine’s alcohol level and, sometimes, its sugar content. (To truly understand the phenomenon, a general understanding of fluid dynamics is helpful.) Legs have no bearing on a wine’s quality, yet Frichette hears the same story again and again.

Many of Frichette’s customers also are convinced that wine, regardless of its age or how it was made, needs to be decanted.

Conversely, Jonathan Pullis, a Master Sommelier and wine director at 7908 Aspen, finds guests reluctant to decant Pinot Noirs, especially aged red Burgundies.

“Guests think it’s too delicate, that the wine will fall apart,” he says. “But these wines are alive, and they need oxygen to wake up.”

Whether to a decant wine, and for how long, depends on a host of factors. The best way to determine what to do is to taste the wine.

If a wine is tight, reticent and not forthcoming, Pullis recommends decanting it for a few hours, and letting the wine slowly warm up to 68°F. However, the process requires familiarity with the wine, an understanding of what makes it “tight” and the right storage conditions.

Color, sulfites and other (un)natural flavorings

In nearly every class he teaches, Erik Segelbaum, founder of wine consultancy Somlyay, listens to stories about sulfite allergies or headaches attributed to their presence in red wine.

“It’s nails on a chalkboard to me,” he says. “People misunderstand what sulfites really are. It’s an organic compound, a natural chemical, that forms naturally during fermentation. All wines have sulfites. Sulfites prevent bacteriological spoilage, kill active yeast and prevent rot.”

While an estimated 1% of people have sulfite sensitivity, the vast majority of folks that feel like crap after they drink wine probably just consumed too much without hydrating.

All kinds of food and drink contain sulfites: dried fruit, charcuterie, beer, soda and French fries. Still, there are very few reports of headaches from sausage or dried apricots. Also, contrary to popular belief, producers tend to add more sulfites to white wines than red, whose tannins work as a preservative. Also, sulfite levels in European wines are just as high as those in U.S. bottlings.

Producers outside the U.S. aren’t often required to slap the disclaimer “contains sulfites” on their labels.

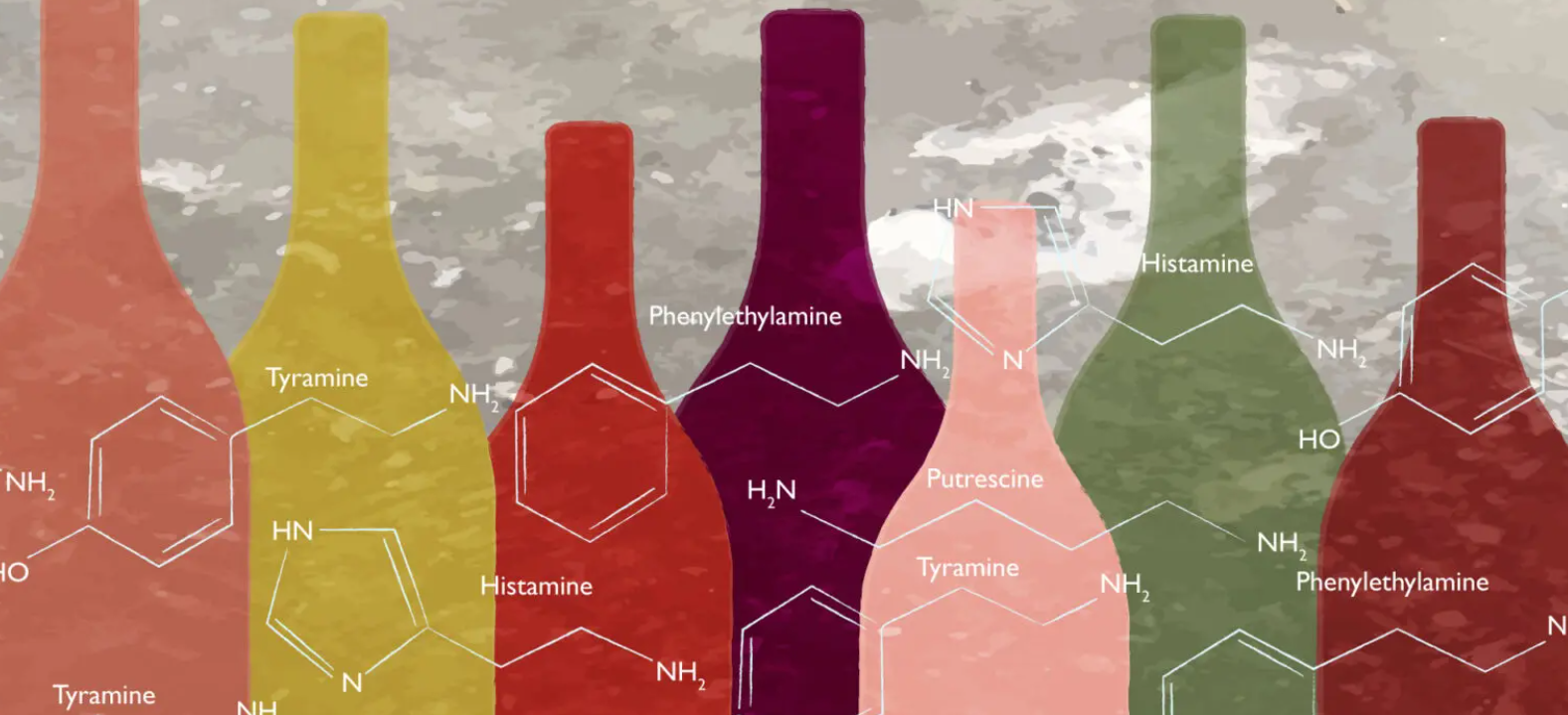

Overindulgence aside, Pullis says wine headaches can stem from any number of things present in wine. “It’s about what’s going on in wine in totality, not just sulfites.”

When Joe Catalino came up in the industry, he was taught one of the biggest myths of all: that wine was made simply from grapes.

“Unfortunately, that isn’t the case when it comes to many wines produced in America,” says Catalino, a Bay Area sommelier and owner of What To Drink. “There are often over 70 additives and chemicals added to wine all the time, including good, old-fashioned white sugar.”

Industrial wineries add flavoring agents, yeast-killing chemicals, acids, saw dust and other ingredients to keep wines consistent from year to year. They also blend in coloring agents. A preference for deep, ruby red hues may play a part in guests who think erroneously that saturated color correlates to quality.

“When I moved to Aspen in 1998, people were holding up red wine glasses and saying in these deep, impressive voices, ‘Look at the color of that wine,’ ” says Pullis.

Cork, bottles and cost

Color is far from the only faux signifier of a wine’s integrity.

Nicolette Diodati, a Wine & Spirit Education Trust (WSET) Level III sommelier and digital marketer for Pernod Ricard, was taught that sniffing a cork would reveal something about a wine’s aroma and caliber, “rather than for cork taint, which is what it can be useful for,” she says.

Diodati was also taught that “the deeper the punt, the better the quality,” referring to the indentation at the bottom of most wine bottles. Though there are several theories, no one really knows why glassblowers began to add punts to wine bottles.

Chad Michael George, founder and bartender of Proof Productions in Denver, wants everyone to know: “The punt on a wine or Champagne bottle should absolutely NOT be used to hold the bottle while pouring. It’s a pointless method and an easy way to drop a bottle on your table.”

Tara Simmons, a fine wine manager at Southern Glazer’s Wine & Spirits, says that many consumers think wines are worth more if they come in heavy bottles, or that there are no good canned wines.

“Heavy bottles are often a marketing decision to make a wine look more expensive,” says Simmons. “And it’s not that the canned wine is secretly good. It’s that a lot of wine that comes in bottles isn’t good. Canned wine is at least honest that it’s an inexpensive, fresh, drink-young option.”

For Segelbaum, the misunderstanding between cost and quality is one of the most frustrating myths in wine. It’s also rampant in the pro community, says Diodati. “Everyone will tell you that price doesn’t equal quality to be [politically correct], but [they] will secretly believe it does.”

While the cost of rare and allocated wines is driven by scarcity, the price of the vast majority of wines is determined by the cost of “input,” which includes land use, oak barrels, labor, labels, bottling, marketing, web hosting, temperature control, shipping and more.

“One acre of plantable land in subprime Napa costs north of $1 million,” says Segelbaum. “A perfect location in Robertson, South Africa, costs $20,000. Every wine is dramatically different.”

Genetics, vineyard sites and AOC's

In wine, there are no hard rules other than those imposed by governing bodies and professional guilds, whose aim is to uphold traditions and standards. But those rules can also create myths.

Diodati says that “a nice man” told her that if she weren’t blessed with a special olfactory system, she’d never be able to smell, taste or understand wine, let alone make it through WSET curriculum.

“Who has a perfect olfactory system?” says Pullis. “The vast majority of people have an average olfactory system, and there are people who can’t taste or smell. Anyone in the normal range can train themselves to be a great taster.”

Frichette gets miffed when she hears, “You can’t grow this here,” especially in Washington, a relatively young wine-growing region still trying to define its terroir. The idea of regional monoculture was the norm in America in the 1970s and ’80s, according to Catalino, but “younger winemakers, as well as legends like Randall Grahm of Bonny Doon, are now experimenting with planting all sorts of cool varieties all over the place.”

Legendary rules and concepts of style, even in the strictest of French Appellations d’Origine Contrôlée (AOCs), are due for questioning. Vin de France, a category once considered near-swill, has been embraced by exceptional producers who, like Frichette, don’t want regulators and tradition to dictate the fruit they grow.

Climate change also is making myths of firmly held notions about where varieties should be grown.

“What worked in the past doesn’t mean it will work in the future,” says Pullis. He cites England’s sparkling wines, whose quality has increased over the last few decades, as well as cooler emerging regions on “the knife’s edge” of achieving ripeness, and recent riper vintages of Burgundy and Sancerre.

“I don’t like to tell people they don’t know things,” says Segelbaum. But sometimes it’s his job to deliver the truth. One of his favorite opening lines for Wine 101 classes is, “I bet you don’t know what taste is.”

Attendees, when goaded, begin to talk about the tongue and taste buds, he says. They throw out words like “sweet,” “sour,” “bitter” and “salty.”

Eventually, he clarifies that 80% of taste is smell. Radicchio, endive and escarole all activate bitter receptors on the tongue. White sugar, turbinado and Splenda light up sweet. But it’s the olfactory system that helps us distinguish one from the other.

“I’m talking to 50 people and telling them, ‘What you know to be true, isn’t true,’ ” says Segelbaum.